A Study of Acts: James Brings His Judgment to the Council

Acts 15:13-21 - I discover lots of big words, struggle through conflicting scholarly viewpoints, and share what James had to say to the Council

“After they had stopped speaking, James answered, saying, “Brethren, listen to me. Simeon has related how God first concerned Himself about taking from among the Gentiles a people for His name. With this the words of the Prophets agree, just as it is written,

‘After these things I will return, And I will rebuild the tabernacle of David which has fallen, And I will rebuild its ruins, And I will restore it, So that the rest of mankind may seek the Lord, And all the Gentiles who are called by My name,’ Says the Lord, who makes these things known from long ago.

Therefore it is my judgment that we do not trouble those who are turning to God from among the Gentiles, but that we write to them that they abstain from things contaminated by idols and from fornication and from what is strangled and from blood. For Moses from ancient generations has in every city those who preach him, since he is read in the synagogues every Sabbath.””

Acts 15:13-21 NASB1995

Well, I quickly discovered when doing research for this fairly short passage that the words that James uses, along with his references to OT prophecy by Amos, are apparently chock-a-block with difficult and widely varying interpretations by Biblical scholars. Suddenly, I was in a world of strange and puzzling phrases, like “spiritualizing” scripture (as opposed to a literal reading), millennialist versus amillennialist viewpoints and dispensationalism. Yikes! We’ll dig into a few of those ideas a little bit more later in this devotional. Since I am now apparently a practitioner of Biblical hermeneutics (another big word) by writing these devotionals, I’m probably obligated to understand and choose how I look at interpretations.

So, let’s start with James. This is the same James who was the half-brother of Jesus (and not the martyred brother of John); he became a believer when Jesus appeared to him after His resurrection. James was the head of the Council in Jerusalem and later wrote the splendid epistle of James. It’s interesting to note that Peter was not the head of the council. James apparently was well-respected by the Jewish believers and was given this role. Precept Austin cites Steven Ger, of Sojourner Ministries for this glimpse of James:

Although he had not been a disciple during his brother's earthly ministry, James became a believer following his Jesus' death, perhaps at the moment when Jesus made an individual post-resurrection appearance to him (1 Cor. 15:7). James led the Jerusalem church for eighteen years, from a.d. 44-62, rising to prominence following the dispersion of most of the apostles to their respective itinerant ministries. Church tradition remembers his nickname of James "the Just," or "the Righteous." Pious, ascetic and devout in his adherence to Torah, he was well esteemed throughout Jerusalem, respected in both Christian and non-Christian circles. Another exceptional church tradition records the detail that his calloused knees were as hard as a camel's from time spent kneeling in prayer. He was the author of the epistle of James, much of which robustly echoes the ethics of his brother's Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5-7). The facility he demonstrates with Greek in his epistle suggests a higher level of education than is commonly assumed was possessed by Galilean craftsmen, leading many to reconsider the impact of the Greco-Roman-Galilean cultural matrix in which James was raised, as well as to revisit our perception of the educational preparation of Jesus. (Twenty-First Century Biblical Commentary – The Book of Acts: Witnesses to the World)

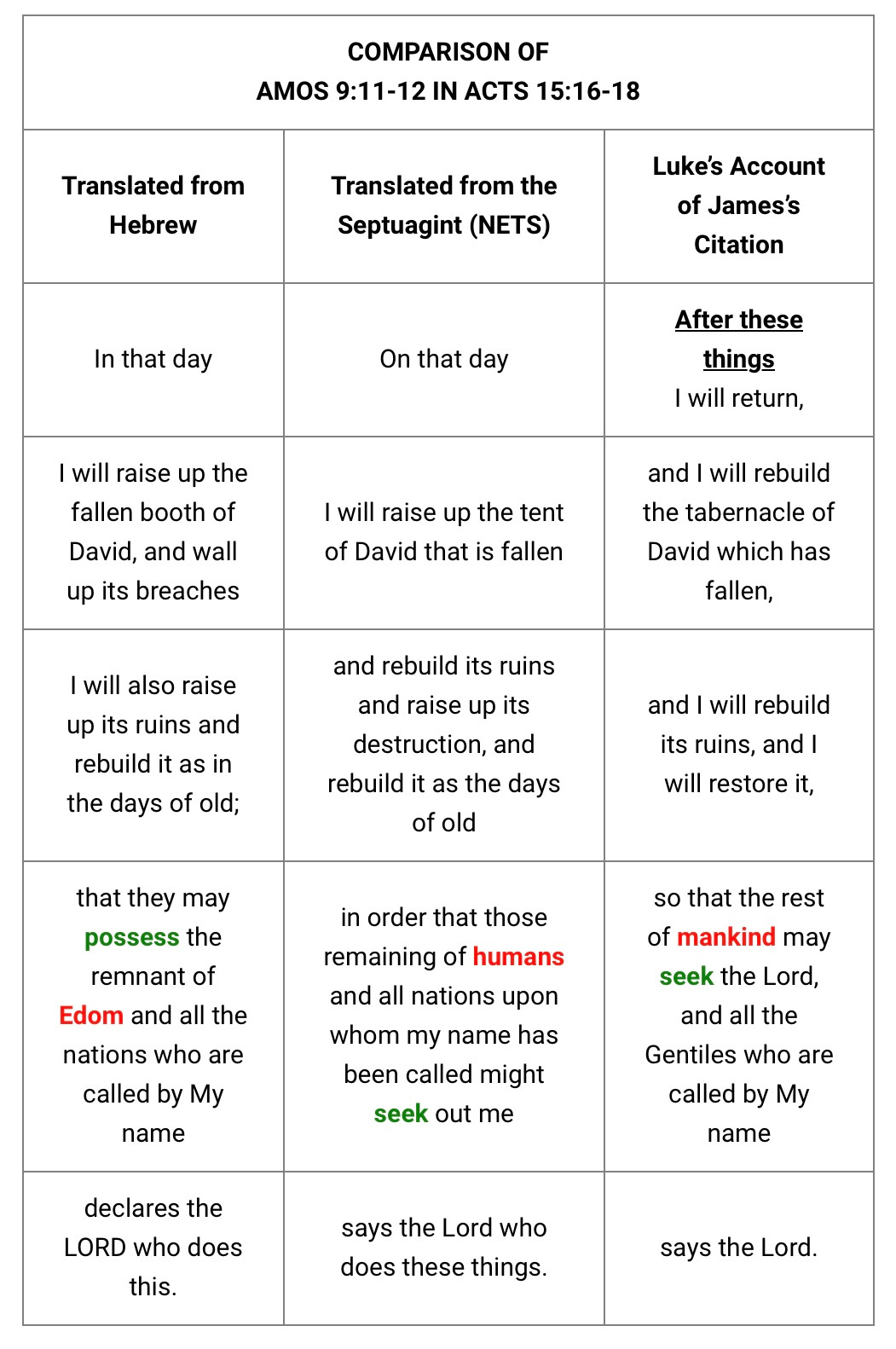

James tells the Council to listen to him and he notes that Simeon (Simon Peter) has related how God has taken from among the Gentiles a people in His name and James agrees with this. James then quotes the prophet Amos. What is interesting about this is that the words from Amos that he quotes are not from the original Hebrew but are from the Septuagint translation, plus they are filtered again through Luke’s transcription. So what is the Septuagint? Here is a short description of the Septuagint from gotquestions.org:

The Septuagint (also known as the LXX) is a translation of the Hebrew Bible into the Greek language. The name Septuagint comes from the Latin word for “seventy.” The tradition is that 70 (or 72) Jewish scholars were the translators behind the Septuagint. The Septuagint was translated in the third and second centuries BC in Alexandria, Egypt. As Israel was under the authority of Greece for several centuries, the Greek language became more and more common. By the second and first centuries BC, most people in Israel spoke Greek as their primary language. That is why the effort was made to translate the Hebrew Bible into Greek—so that those who did not understand Hebrew could have the Scriptures in a language they could understand. The Septuagint represents the first major effort at translating a significant religious text from one language into another.

Precept Austin has conveniently created a table that shows the three different versions of Amos 9:11-12 (the verses quoted by James) - Precept Austin uses the same translation of the Bible that I use (NASB1995).

So this is where things got a little bit tricky in my research. Essentially (bottom line), what James is saying is that he believes that both the Jews and the Gentiles are saved by faith alone in God or Christ alone. But many scholars ended up going down all sorts of bunny trails on what it means to rebuild the tabernacle and “when I return”. To show you my dilemma, I want to do another excerpt from Precept Austin citing Dr. Thomas Constable (formerly from the Dallas Theological Seminary); I believe some of the words are also from the author of Precept Austin:

1) Some interpreters believe James meant that the inclusion of Gentiles in the church fulfilled God’s promise through Amos (RCH Lenski). These (generally amillennial) interpreters see the church as fulfilling God’s promises to Israel. This view seems to go beyond what Amos said since his prophecy concerns the tabernacle of David, which literally interpreted would involve Israel, not the church.

(2) A second group of interpreters believe James meant that God would include Gentiles when He fulfilled this promise to Israel in the future. However there was no question among the Jews that God would bless the Gentiles through Israel in the future. The issue was whether He would do this apart from Judaism, and this interpretation contributes nothing to the solution of that problem. This view does not seem to go far enough.

(3) A third view is that James meant that the present inclusion of Gentiles in the church is consistent with God’s promise to Israel through Amos. The present salvation of Gentiles apart from Judaism does not contradict anything Amos said about future Gentile blessing. This seems to be the best interpretation.

In other words, James says, God is working out His own plan: Israel, His covenant people have been set aside nationally because of their rejection of the Messiah. God is now taking out a people, Jew and Gentile, to constitute the Church of God. When He completes this work, the Lord is coming back the second time. That will be the time of blessing for the whole world [i.e., the millennial reign of Christ].

James added the quotation from Isaiah 45:21 in verse 18b probably to add authority to the Amos prophecy.

The thought that the church was the divinely intended replacement for the temple is probably to be seen in 15:16–18.

The non-dispensational understanding of this text is that James was saying that the messianic kingdom had come and Amos’ prediction was completely fulfilled. Progressive dispensationalists believe he meant that the first stage of the messianic kingdom had come and that Amos’ prediction was partially fulfilled. Normative dispensationalists view the messianic kingdom as entirely future. They believe Amos was predicting the inclusion of Gentiles in God’s plan and that James was saying that the present situation was in harmony with God’s purpose. Thus the Amos prediction has yet to be fulfilled.

Deciding between these options depends on whether or not one believes the church replaces Israel in God’s plan. If it does, one will side with non-dispensationalists here. If one believes the church and Israel are distinct in the purpose of God, then one has to decide if there is better evidence that Jesus has begun to rule over David’s kingdom now (progressive dispensationalism) or not (normative dispensationalism). I believe the evidence points to the fact that David’s kingdom is an earthly kingdom and that Jesus will begin reigning over it when He returns to earth at His second coming.

OUCH!! My head hurts! I’ve stumbled across some of these arguments and words before and quickly skated away, but it seems like it’s finally time to pay the piper and actually review a few terms and try to learn. Now I know why so many pastors pay the big bucks to go to seminary school, because there they have to learn these things and filter into their preaching their particular Biblical viewpoint. I will rely on my good friends at Gotquestions.org:

First, dispensationalism:

A dispensation is a way of ordering things—an administration, a system, or a management. In theology, a dispensation is the divine administration of a period of time; each dispensation is a divinely appointed age. Dispensationalism is a theological system that recognizes these ages ordained by God to order the affairs of the world. Dispensationalism has two primary distinctives: 1) a consistently literal interpretation of Scripture, especially Bible prophecy, and 2) a view of the uniqueness of Israel as separate from the Church in God’s program. Classical dispensationalism identifies seven dispensations in God’s plan for humanity.

Dispensationalists hold to a literal interpretation of the Bible as the best hermeneutic. The literal interpretation gives each word the meaning it would commonly have in everyday usage. Allowances are made for symbols, figures of speech, and types, of course. It is understood that even symbols and figurative sayings have literal meanings behind them. So, for example, when the Bible speaks of “a thousand years” in Revelation 20, dispensationalists interpret it as a literal period of 1,000 years (the dispensation of the Kingdom), since there is no compelling reason to interpret it otherwise.

There are at least two reasons why literalism is the best way to view Scripture. First, philosophically, the purpose of language itself requires that we interpret words literally. Language was given by God for the purpose of being able to communicate. Words are vessels of meaning. The second reason is biblical. Every prophecy about Jesus Christ in the Old Testament was fulfilled literally. Jesus’ birth, ministry, death, and resurrection all occurred exactly as the Old Testament predicted. The prophecies were literal. There is no non-literal fulfillment of messianic prophecies in the New Testament. This argues strongly for the literal method. If a literal interpretation is not used in studying the Scriptures, there is no objective standard by which to understand the Bible. Each person would be able to interpret the Bible as he saw fit. Biblical interpretation would devolve into “what this passage says to me” instead of “the Bible says.” Sadly, this is already the case in much of what is called Bible study today.

Dispensational theology teaches that there are two distinct peoples of God: Israel and the Church. Dispensationalists believe that salvation has always been by grace through faith alone—in God in the Old Testament and specifically in God the Son in the New Testament. Dispensationalists hold that the Church has not replaced Israel in God’s program and that the Old Testament promises to Israel have not been transferred to the Church. Dispensationalism teaches that the promises God made to Israel in the Old Testament (for land, many descendants, and blessings) will be ultimately fulfilled in the 1000-year period spoken of in Revelation 20. Dispensationalists believe that, just as God is in this age focusing His attention on the Church, He will again in the future focus His attention on Israel (see Romans 9–11 and Daniel 9:24).

Dispensationalists understand the Bible to be organized into seven dispensations: Innocence (Genesis 1:1—3:7), Conscience (Genesis 3:8—8:22), Human Government (Genesis 9:1—11:32), Promise (Genesis 12:1—Exodus 19:25), Law (Exodus 20:1—Acts 2:4), Grace (Acts 2:4—Revelation 20:3), and the Millennial Kingdom (Revelation 20:4–6). Again, these dispensations are not paths to salvation, but manners in which God relates to man. Each dispensation includes a recognizable pattern of how God worked with people living in the dispensation. That pattern is 1) a responsibility, 2) a failure, 3) a judgment, and 4) grace to move on.

Dispensationalism, as a system, results in a premillennial interpretation of Christ’s second coming and usually a pretribulational interpretation of the rapture. To summarize, dispensationalism is a theological system that emphasizes the literal interpretation of Bible prophecy, recognizes a distinction between Israel and the Church, and organizes the Bible into different dispensations or administrations.

Ok, digest that for a while. Now, how about premillennialism (this is a very short introductory definition)?

Premillennialism is the view that Christ’s second coming will occur prior to His millennial kingdom, and that the millennial kingdom is a literal 1000-year reign of Christ on earth. In order to understand and interpret the passages in Scripture that deal with end-times events, there are two things that must be clearly understood: a proper method of interpreting Scripture and the distinction between Israel (the Jews) and the church (the body of all believers in Jesus Christ).

Since I usually avoid eschatology like the plague, perhaps this is good for me, as I am contemplating diving into the Book of Daniel next. Please note that Gotquestions.org bases their answers and theology on a literal interpretation, dispensationalism and premillennialism perspective. They did provide this definition for amillennialism, which is not considered heretical in their viewpoint, but is another interpretation that has been broadly accepted (this is a partial excerpt):

An amillennialist sees the 1,000 years as spiritual and non-literal, as opposed to a physical understanding of history. Although the prefix a- would typically signify a negation of a word, the amil position sees the millennium as “realized,” or better explained as “millennium now.” To simplify, amillennialism sees the first coming of Christ as the inauguration of the kingdom, and His return as the consummation of the kingdom. John’s mention of 1,000 years thus points to all things that would happen in the church age.

….

There are many arguments against the amillennial position, but they can be refuted through exegesis of Scripture. Careful hermeneutics (the study of the principles of interpretation), proves the amil position has legitimacy. Most passages of Scripture used to try to refute the position actually make it more viable, based on the words of our Lord Himself: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matthew 5:17). In light of the words of our Savior, prophetic passages like Daniel 7 and Jeremiah 23 are to be understood as fulfilled in Christ Jesus and His first coming, especially since all of the prophets are talking about the coming Messiah in the first place.

Jesus fulfilled all the prophecies concerning Him, including, for example, the prophecy that Christ’s feet will touch the Mount of Olives prior to the establishment of His kingdom (Zechariah 14). This was clearly fulfilled in Matthew 24 when Jesus went to the Mount of Olives to teach what is known as the Olivet Discourse.

In amillennialism, the “1,000 years” is happening right now. Christ’s work in this world—His life, death, resurrection, and ascension—greatly hindered the works of Satan so that the message of the gospel could leave Israel and go out to the ends of the earth, just as it has done. The 1,000 years spoken of in Revelation 20, in which Satan is “bound,” is figurative and fulfilled in a spiritual sense. Satan is “bound” in that he is restricted from implementing all his plans. He can still perform evil, but he cannot deceive the nations until the final battle. Once the “1,000 years” are over, Satan is released to practice his deception for a little while before the return of Christ.

So if you want to pin me down, I think I can probably say that I am more inclined towards being a premillennial dispensationalist who believes there is a separate promise by God to Israel and Christians and who also doesn’t believe in Cessationism (the end of miracles after the early church). So there!

Let’s get back on the trail. James opened a giant can of worms that we still see being discussed and argued about 2,000 years later. After his citation of Amos, he passes on instructions to Gentile Christians, after acknowledging that they should not trouble them to follow Mosaic law:

Abstain from things contaminated by idols.

Abstain from fornication (sexual immorality).

Abstain from eating something that is strangled.

Abstain from eating blood.

Huh?? Well, the point of these admonitions (which are not required for salvation) was to make it easier for the missionaries to preach to both the Jews and the Gentiles by requesting that the Gentiles not do really obnoxious things that would cause dissension between the groups if they happened to come together for worship or a meal (three of the four were concerning dietary hospitality). Here’s what Enduring Word says about this passage:

We should not trouble those from among the Gentiles who are turning to God: James essentially said, “Let them alone. They are turning to God, and we should not trouble them.” At the bottom line, James decided that Peter, Barnabas, and Paul were correct, and that those of the sect of the Pharisees who believed were wrong.

“The Protestant Reformers wisely and insistently pointed out that councils have erred and do err. They have erred throughout history, and they continue to err today…But God blessed it nevertheless, and he has often done with the formal meetings of sinful human beings who nevertheless gather to seek God’s will in a matter.” (James Montgomery Boice)

But that we write to them to abstain from things polluted by idols, from sexual immorality, from things strangled, and from blood: James’ decision that Gentile believers should not be under the Mosaic Law was also given with practical instruction. The idea was that it was important that Gentile believers did not act in a way that would offend the Jewish community in every city and destroy the church’s witness among Jews.

If the decision was that one did not have to be Jewish to be a Christian, it must also be said clearly that one did not need to forsake the Law of Moses to be a Christian.

To abstain from things polluted by idols… from things strangled, and from blood: These three commands had to do with the eating habits of Gentile Christians. Though they were not bound under the Law of Moses, they were bound under the Law of Love. The Law of Love told them, “Don’t unnecessarily antagonize your Jewish neighbors, both in and out of the church.”

To abstain from… sexual immorality: When James declared that they warned the Gentile Christians to abstain from… sexual immorality, we shouldn’t think that it simply meant sex outside of marriage, which all Christians (Jew or Gentile) recognized as wrong. Instead, James told these Gentiles living in such close fellowship with the Jewish believers to observe the specific marriage regulations required by Leviticus 18, which prohibited marriages between most family relations. This was something that would offend Jews, but most Gentiles would think little of.

To abstain from: Gentile Christians had the “right” to eat meat sacrificed to idols, to continue their marriage practices, and to eat food without a kosher bleeding, because these were aspects of the Mosaic Law they definitely were not under. However, they were encouraged (required?) to lay down their rights in these matters as a display of love to their Jewish brethren.

“All four of the requested abstentions related to ceremonial laws laid down in Leviticus 17 and 18, and three of them concerned dietary matters which could inhibit Jewish-Gentile common meals.” (John Stott)

My next devotional examines Acts 15:22-35 - Agreement is reached and a letter is prepared for Gentile believers. Paul and Barnabas return to Antioch.

Heaven on Wheels Daily Prayer:

Dear Lord - We humans have created lots of big words and different perspectives on Your Word and Your promises. I humbly pray that I simply believe and trust! Amen.

Scripture quotations taken from the (NASB®) New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1971, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. All rights reserved. lockman.org

Precept Austin was accessed on 11/16/2024 to review commentary for Acts 15:13-21.

Gotquestions.org was accessed on 11/16/2024 (multiple times) to review the answers to questions about the Septuagint, Dispensationalism, Premillennialism and Amillennialism.

Commentary from Enduring Word by David Guzik is used with written permission.